- Home

- Susan Kiernan-Lewis

Little Death by the Sea Page 29

Little Death by the Sea Read online

Page 29

The eerie obelisks and weathered tombstones, washed in the light of dusk, shot irregular shadows in every direction, like spirits leaping out in confusion and panic. Maybe this wasn’t such a hot idea, Maggie thought.

She moved between the headstones, careful not to trample the flowers that attentive mourners had placed next to the graves, and took a seat on one of the many wrought iron benches, its scroll work was intricate and lovely. She thought for a moment of the ancient artisan commissioned to create these graveyard thrones. She wondered what his thoughts had been as he worked.

The cemetery did not frighten her, although it did give her a vague sense of unease. Lost or earth-bound souls were not much of a consideration for Maggie. Never had been, she mused, as she thought of her father telling her and Elise ghost stories when they were girls. Elise seemed to want to believe in witches and spirits and supernatural things. Elise had paid close attention to her father’s stories, jumping in the appropriate spots, eyes widening in exquisite fright to his delight. Maggie hadn’t seen the point. If someone was dead, he was dead. She’d thought so then. She thought so now. Elise had always told her she had no imagination.

Maggie turned to find the window of Elise’s apartment, the window where her sister had painted her watercolors, written her letters. Gone forever, Maggie thought. Elise gone, her little girl gone. And here she was, Maggie, sitting directly in the scene Elise had painted maybe a hundred times. Maggie touched a nearby headstone and felt its hard smoothness. It was marble, and icy-cold, but looked like old chalk, crumbling and dirty.

Why had she come here? To say good-bye to Elise? Why not the Elise who had lived in the Latin Quarter? At least that was an Elise she might have understood.

Maggie’s eyes filled and she opened her purse to search for a tissue. And, of course, the Latin Quarter Elise was an Elise who hadn’t felt at all understood. She was an Elise who’d packaged herself in such a way as to be accepted by her family—but who had compromised herself to do it. This was the real Elise, Maggie realized, the one who had lived in Montmartre and taken drugs and brutal lovers. Wild and free and too different to be honestly loved by her family, this Elise had painted. And died. For, surely, Michele was right: Elise had died here long before she ever went to Atlanta.

Maggie pulled out of her purse the glittering goldtone scarf ring Brownie had given to her at Nicole’s birthday party. She thought of that little girl and her heart squeezed. What is Nicole’s real name? she wondered. Who is she? Maggie sat on the hard little bench, her lap full of the contents of her purse, and felt a light breeze touch her skin. It was getting late.

Shaking herself, she began to put everything back into her purse. Plenty of time for all of those questions, she told herself. Her time in Paris was through. She’d done what she had come to do. And more, she thought, as a picture of Laurent came to mind. She held the little scarf ring in her hand for a moment and thought of Brownie. Poor Brownie wanted to help so much. He wanted to be a part of her world so very much.

Suddenly, looking at the little gold-painted scarf ring, Maggie felt a realization so swift, so undeniable, that she nearly gasped when it hit her. She held the scarf ring tightly in her fingers and stared at it.

She knew who Elise’s murderer was.

Chapter 21

1

Darla stared at the map propped up against her coffee cup. Gerry had drawn loopy black lines on the map of Auckland City to indicate areas where they might live in, where he would work, where Haley might attend school. Darla touched a spot on the map. Kohimarama.. She traced the line across Hobson Bay. One Tree Hill. Onehunga. Te Papapa. Her finger came to a stop at Manukau Harbor.

“Finding everything all right?” Gerry dried his hands on a dishtowel and leaned over the back of his wife’s chair. He smelled of soap and coffee beans.

Darla withdrew her finger and placed her hands in her lap.

“See, this is Waitemata Harbor.” He jabbed at an expanse of blue that divided the city of Auckland. “If I take the Bates’ job, I’ll be able to see the water from my office. They’ve got a regatta every Wednesday in full view. That’s what the headhunter said. Pretty neat, eh?”

Darla sighed loudly.

“Or maybe you don’t think so.” Gerry tossed the kitchen towel down onto the table and pulled his jacket from the back of one of the kitchen chairs.

Darla lifted up a corner of the map and felt under it for her cooling coffee. Gerry pulled on his suit jacket, jerking the cuffs down and pushing the front together, although not buttoning it.

“If we get a place in Remuera, for example, there’s a good school for Haley there.”

“Your headhunter said so.” Darla spoke softly as she brought the coffee cup to her lips.

“Interesting name, Remuera. Maori, I suppose. Wonder what it means, don’t you?” Gerry adjusted his tie, jutting his chin out like a startled turkey stretching at a sudden sound.

“When will you be back?” Darla picked up the map and began to fold it. Gerry watched the precise movements which demonstrated an unusual deliberateness for his wife—usually so fast and slap-dash.

He shrugged and peered around the corner of the kitchen into the living room as if searching for something.

“Tomorrow afternoon,” he said. “I’ll get there around eight or so, I guess. Meet with Bryant for dinner...God, it’s going to be a late night.”

“You think he’ll buy you out of Selby’s?” The map crinkled noisily in her fingers. He thought it was taking her a long time to get it all folded up.

“We shall see,” he said breezily. “Seen my briefcase?”

She said nothing. Holding the map tightly in her hand, she sat and looked vacantly at the kitchen wall opposite her.

“Should be back, everything wrapped up, by tomorrow afternoon,” he repeated, “I’ll call you, of course.”

“Going to wrap up everything before Maggie’s had a say?”

Gerry stopped hunting for his briefcase and looked at his wife. He needed to get this over and done with, he thought. The sooner moved, the sooner adjusted.

“She knows I’m talking to a guy.”

“She know you intend to sign on the dotted line?”

“I’m not sure I do intend to.”

She turned in her chair and looked at him. He thought she looked frightened. I’m doing this for you, Darla!

“Okay, I do intend to,” he said. “But it can’t be helped. Maggie knows that. She knows how important this is to me. I wouldn’t sell her down the river.” He pulled up a chair and sat down next to his wife. “If this guy isn’t right for Selby’s, I won’t sell. You believe that, don’t you?”

She stared into his eyes, then dropped the map onto the table and put her hand up to his freshly-shaved cheek.

“I love you, Gerry,” she said, beginning to cry.

He put his arms around her.

“Believe in me, Darla,” he said. “Believe I’m doing what’s best for all of us.”

She buried her face into his suit jacket.

2

The taxi driver gave Maggie an impatient toot on his horn. Maggie turned to glare at him from where she stood outside the hotel in a telephone booth. I’m so sick of these people! She gripped the telephone receiver a little tighter.

“Une moment!” she shouted, forcing a feigned smile in his direction. Her bag was sitting in the backseat of the taxi and she wasn’t totally convinced he wouldn’t take off with it just to show the impertinent American that he could not be kept waiting. Weren’t we on the same side during the war? she wondered. Didn’t we help liberate bloody Paris?

“Sorry, M’am,” the voice crackled over the telephone wire to her. “Detective Burton isn’t answering his page either.”

Maggie shifted the phone receiver to her other ear.

“I’ve got to talk to him.” She closed her eyes in agony. “I have got to speak to the detective.”

“You’ll have to leave a message.” The impersonal dron

e of the sergeant’s voice served to increase her agitation.

“A message? God, what kind of...” She took a deep breath and looked briefly in the direction of the angry taxi driver. “Look, tell Detective Burton or Detective Kazmaroff that Margaret Newberry called again, okay?” She paused until she was sure the man was writing this all down. “Tell him, please, that I know who killed my sister. And Dierdre Potts, too. Tell him that. And...and to page me at the Paris airport, okay? I’ll be there in about thirty minutes and for about an hour once I’m there. Charles DeGaulle airport in Paris. Okay?”

I must be mad to think that redneck cop is going to call the airport in Paris, France, she thought, pushing a hand through her hair. She heard the sound of the taxi driver’s door slamming shut and she turned back to the phone.

“Look, just give him my message and have him call me, please.” She hung up on the sergeant’s assurances that he would give Burton her message. She hurried down the stone steps of the Hotel L’Etoile Verte and greeted the indignant taxi driver.

“Sorry! Sorry!” she sang breathlessly as she tugged open the passenger door of his taxi. “Je me regret! Je m’excuse!”

The man grunted and returned to his side of the car. He poked viciously at his watch as if to indicate that he would be charging Maggie for the extra time spent waiting for her.

Maggie climbed into the back seat and tossed her purse to the far side in an exhausted gesture. She had tried last night and most of this morning to reach either Jack Burton or Dave Kazmaroff to tell them of her discovery. The police department had refused, understandably, to give out their home phone numbers, and the pair had been unavailable for the last twenty hours or so.

Maggie told the driver to take her to Charles DeGaulle Airport and then sank into the stained and lumpy backseat.

3

She drummed her fingers on the Delta Airlines countertop, unaware of the annoyed look the pretty flight clerk was giving her.

“Here’s your passport, Mademoiselle,” the clerk said to her, handing back her American passport. “We hope you have enjoyed your stay in Paris?”

Maggie looked at her uncomprehendingly. “Huh?”

“Your flight leaves Gate Five, please. Thank you,” the clerk said, looking beyond her to the person next in line.

“Oh, okay, thanks.” Maggie gathered up her carry-on bag and stuffed her passport and ticket into the side pocket of her purse. She moved out of line, her ears straining to catch the sound of her name being paged over the public address system.

Charles DeGaulle was chaos. Drug-sniffing German shepherd dogs roamed aggressively at the ends of taut leashes held by uniformed officials, signs insisted from every doorway that passengers should not leave their bags unattended for a single moment, crying children seemed to be everywhere—either attached to sour-faced mothers or roaming pitifully alone, presumably in search of sour-faced mothers.

Maggie pushed through the crowd and tried to remember the excitement and anticipation she had felt just a few days ago when she had landed here from Atlanta. Then, the airport had seemed abuzz with hope and promise, a traveler’s way station of rare adventure about to happen. This morning, she saw the filth on the floors and the distrust in her fellow traveler’s eyes. It made her shiver all the way through her double-quilted bomber jacket.

She took a place at the back of the line that wrapped around the Information Desk and checked her watch. She had a full hour before take-off, and still no word from Atlanta. She hoisted her carry-on bag to her other shoulder and tried to take mental refuge in the stillness of the queue from the roiling, noisy crowd moving and milling around her

Why wasn’t he paging her? Was her message not forceful enough? My God! I said I’ve discovered the identity of the killer, is that not strong enough? Maggie eyed the woman manning the information booth and hoped she spoke English. Should she have left a message actually naming the killer? Was it safe to do that? She looked at her watch again. It was late afternoon back home. Where had the detectives been all day? Will I need to prove that what I say is true? She had an uncomfortable image of Burton crumpling up her message and tossing it away. “Not that Newberry woman again! Why doesn’t she give it a rest? ‘Found the killer’, she says! Brother!”

Maggie looked around the rotund German hausfrau standing stolidly in front of her in line to the pinch-faced woman behind the booth. The woman didn’t look to Maggie to be particularly helpful. Suddenly, she felt a permeating weariness creep over her. She was so sick of trying to make people give her information or help her. A garbled message in French came over the public address system, and Maggie strained to catch some semblance of her name being mentioned. In frustration and relief, she finally approached the counter.

“My name is Margaret Newberry,” she said breathlessly. “I am expecting a page.”

“Your question?” The woman looked at her coldly.

This is it! I’m going to kill a human being in an international airport!

“What part did you not understand, Madame?” Maggie said testily. “The pronunciation of my name? Mar-gar-et New-berry. Comprenez?”

“There have been no pages for you.”

“Thank you. You’ve been a dear.” Maggie scowled at the woman, enjoying the perverse pleasure of finally not having to force a sociability she was long-past being able to feel. She turned away from the counter, frustrated and defeated. She walked toward the long corridor that led to her departure gate.

Maggie turned quickly to the wall of telephones that lined the tiled boulevard within Charles DeGaulle Airport. She deposited her bag against the wall and jammed a franc coin into the machine. She had been crazy to withhold the name of the killer in her messages to Burton and Kazmaroff. She had been so sure that Burton would doubt her word that she had held off naming the murderer until she could do it on the phone to him herself—outlining her detailed evidence, sketching out her argument. But, apparently, not having the name to work with only seemed to ensure that Burton disregarded her messages. She had to tell him what she knew and pray he would take it from there.

When the same bored Fulton County desk sergeant came on the line, Maggie was brief. “Look, this is Margaret Newberry again—“

“Detectives Burton and Kazmaroff are not in, Miss Newberry. They have not seen your messages—“

“Do they call in for their messages from time to time, I wonder?”

“I will deliver your messages to them as soon as—“

“Look, forget it. I have a new message.”

There was an audible sigh on the other line.

“Shoot,” he said.

“Tell Burton this,” Maggie licked her lips and watched the traveler’s parade by her—nasty raincoats and broken-down umbrellas, patched-together satchels accented by the wicked slickness of leather micro-skirts and peeled-back hairlines. “Tell him the key is Gerry Parker. You got that?” Maggie turned away from the stream of airport travelers and faced the phone box. “All the victims are connected to him. Tell Burton that Maggie said ‘Stump did it’.”

4

A haphazardly taped flap of the box that held every piece of her wedding china began to slowly curl up as if repelled by its own adhesive powers. Darla watched it from the kitchen table where she was in the process of packing another box. She made a mental note to repair it later and turned back to the box on the table in front of her. Carefully, she placed a ten-inch ceramic Madonna-and-child, which she and Gerry had found on their honeymoon nine years ago, in a nest of tissue and newspaper. The Madonna’s head was cocked as if questioning her. Are you really going through with this? it seemed to ask. Darla tried to imagine this box, with its fragile, hidden prize, in the bowels of some rusting tramp steamer making its tedious, laborious way across the Pacific Ocean, past atolls, uninhabited islands, radiation-cooked archipelagos, and ancient shipwrecks to the lonely little apostrophe of a country in the middle of the sea, at the bottom of the world. She looked around her kitchen and saw the boxes stack

ed against the counters, crowding the butcher’s block table, obstructing nearly every passageway to and from the kitchen—normally the room with the highest traffic in the house.

Darla’s kitchen—warm and country with its wooden spoons on the walls and beribboned, macraméd potholders—had been where the family congregrated for “comfort foods”, for standing around and talking about what happened in school, at work. There was always a pot of coffee bubbling, a freshly-iced layer cake on the counter, the lovely, lilting aroma of something delicious just removed from the oven.

Gerry had even cleared the refrigerator of magnets.

The house was quiet this afternoon. Darla had allowed Haley to spend the night with a friend although she had been tempted to keep her daughter home for company. But the weeks were racing away when Haley would still be able to see her friends and Darla couldn’t deny her much during these last hard weeks before the move.

“Your father and I would move without batting an eyelash.” Her mother, the stereotypical Army wife, had called earlier in the day to see how the packing was coming. As Darla had expected, her mother could see no reason for Darla’s reluctance, let alone resistance, to the idea of moving. “Guam, Germany, California...”

“I know, Mom, I know,” Darla had argued, “but you and Dad did your moving before we kids were born.”

“So? We certainly didn’t plan it that way. The service won’t let you, you know. You go when and where they tell you to go. And Gerry needs to do this for his career, and you, as a good—“

“It’s not for his career, Mom!” Darla had wanted to rip the phone out of the wall. Was everyone ready to see her in a covered wagon, forging ahead to some primitive new land...at the bottom of the world? “He doesn’t even have a job down there. He’s just doing it out of fear.”

“Darla, I don’t like to hear you talk like that. A wife should support her husband. Not snipe behind his back, dear.”

Darla wanted to weep, and she had already done plenty of that. She shoved another empty box onto the kitchen table and began rummaging around for more newspaper. Some days she thought she could really make it work, could stop fighting with Gerry about it and just get in step with him. Other days, she cried.

Free Falling, Book 1 of the Irish End Games

Free Falling, Book 1 of the Irish End Games Murder in the South of France, Book 1 of the Maggie Newberry Mysteries

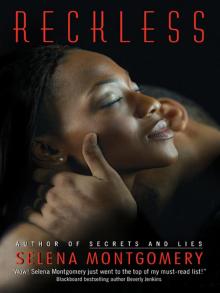

Murder in the South of France, Book 1 of the Maggie Newberry Mysteries Reckless

Reckless The Complete Maggie Newberry Provençal Mysteries 1-4

The Complete Maggie Newberry Provençal Mysteries 1-4 Murder à la Carte (The Maggie Newberry Mystery Series)

Murder à la Carte (The Maggie Newberry Mystery Series)![[Tempus Fugitives 01.0] Swept Away Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/23/tempus_fugitives_01_0_swept_away_preview.jpg) [Tempus Fugitives 01.0] Swept Away

[Tempus Fugitives 01.0] Swept Away Murder in the South of France: Book 1 of the Maggie Newberry Mysteries (The Maggie Newberry Mystery Series)

Murder in the South of France: Book 1 of the Maggie Newberry Mysteries (The Maggie Newberry Mystery Series) Little Death by the Sea

Little Death by the Sea A Trespass in Time

A Trespass in Time Free Falling

Free Falling